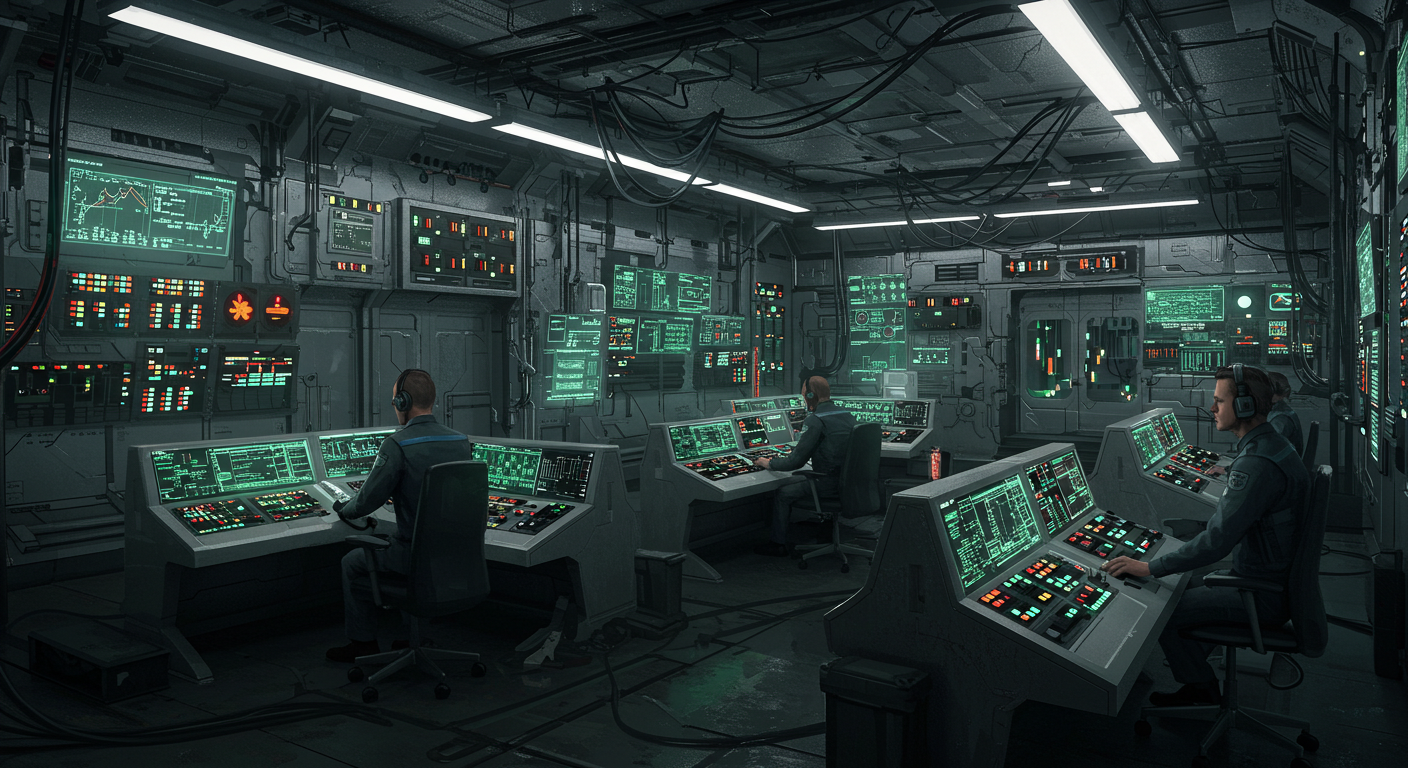

In the glow of a control room, data flows like a river—constant, complex, and ceaseless. Graphs rise and fall, maps pulse with activity, alerts blink with quiet urgency. But behind every dashboard, behind every interface, sits a human being. Not a machine. Not an algorithm. A person—breathing, thinking, interpreting, deciding. And it is this human presence that transforms raw information into meaningful action.

Modern operations often speak of automation, artificial intelligence, and real-time analytics as if they render human involvement obsolete. But those who manage mission-critical environments know the truth: technology amplifies human capability—it does not replace it. The most advanced monitoring system is only as effective as the operator who understands its language, senses its anomalies, and acts on its insights. And for that operator to perform consistently, the environment must be shaped around their needs—not the other way around.

This is where the philosophy of user-centric design reveals its quiet power. It is not about aesthetics or convenience. It is about cognitive alignment—ensuring that the layout of screens, the logic of workflows, and the ergonomics of workstations all serve the natural rhythms of human perception and decision-making. A well-designed console doesn’t just look clean; it reduces mental load. A thoughtfully placed control doesn’t just save time; it prevents hesitation in critical moments. Even the ambient temperature and lighting are calibrated not for comfort alone, but for sustained alertness.

Operator well-being, then, is not a peripheral concern—it is central to operational integrity. Fatigue, distraction, and discomfort are not personal inconveniences; they are systemic vulnerabilities. A stiff neck from a poorly angled monitor can delay a response. Glare on a screen can obscure a warning. A confusing interface can lead to misinterpretation. These are not minor issues. In high-stakes environments, they are the thin line between stability and failure.

That’s why the most effective control environments are built through integrated thinking—where engineering, human factors, and operational goals converge from the earliest stages of planning. It’s not enough to install powerful software or high-resolution displays. The entire ecosystem must be orchestrated: from the acoustics that minimize auditory stress, to the furniture that supports posture over long shifts, to the color schemes that enhance data readability without causing visual fatigue.

This holistic approach reflects a deeper respect for the human role in complex systems. It acknowledges that operators are not interchangeable components, but skilled professionals whose performance is deeply influenced by their surroundings. When those surroundings are designed with intention—when every element serves clarity, efficiency, and comfort—the result is not just better morale, but better outcomes.

And yet, this success is often invisible. When a power outage is averted, when a transportation delay is minimized, when a security threat is neutralized before escalation—no one credits the chair, the lighting, or the interface layout. But those who work in the room know: the environment was a silent partner in that success.

In a world racing toward full automation, the control room stands as a quiet reminder that human judgment remains irreplaceable. Machines process data. Humans understand context. Algorithms detect patterns. Operators sense the outliers. And for that irreplaceable human element to thrive, the space must be more than functional—it must be fundamentally human.

So the next time you benefit from seamless infrastructure—a smooth commute, uninterrupted power, rapid emergency response—remember: somewhere, a human is watching. And the room around them was built not just to house technology, but to honor the one who wields it.