In the rhythm of mission-critical operations, there exists a space that is rarely measured but always felt—the space between data and decision. It is not physical, yet it is shaped by physical design. It is not technical, yet it is influenced by technology. It is the cognitive gap where information becomes insight, where observation becomes action, and where the environment either supports clarity or obscures it.

This space is where operators live for hours at a time. Not in front of screens, but within them—immersed in streams of metrics, alerts, and visualizations that must be interpreted under pressure, often with incomplete information. Their performance does not depend solely on training or experience, though both matter deeply. It also depends on the room around them: the angle of a monitor, the color of a dashboard, the depth of a chair, the quality of light, the absence of distraction. These are not background details. They are active participants in the decision-making process.

When a control environment is designed with operator well-being as a core principle, that space between data and decision narrows. Cognitive load decreases. Reaction time sharpens. Fatigue recedes. This is not speculation—it is human factors science in practice. A screen positioned at optimal eye level reduces neck strain and maintains visual focus. A high-contrast interface minimizes misreading under stress. Ambient lighting tuned to circadian rhythms sustains alertness without glare. Even the acoustics of the room—engineered to absorb rather than echo—contribute to a state of calm concentration.

This philosophy reflects a deeper truth: that efficiency in critical operations is not just about faster systems, but about clearer humans. Technology can deliver data at lightning speed, but if the operator is physically uncomfortable, visually overwhelmed, or mentally fatigued, that speed is wasted. True operational excellence emerges when the human element is not accommodated as an afterthought, but centered from the beginning.

That centering begins long before construction. It starts in the consultation phase, where workflows are observed, pain points are noted, and operator feedback is gathered not as input, but as insight. It continues through design, where every layout decision is tested against real-world scenarios. It extends into implementation, where furniture, lighting, and interfaces are calibrated not to generic standards, but to the specific rhythms of the team that will use them. And it endures through support, where refinements are made based on lived experience—not assumptions.

This is integrated project management in its most meaningful form: not just coordinating tasks, but aligning disciplines around a shared understanding of human performance. Engineering, ergonomics, software, and architecture do not operate in silos. They converge to serve a single goal—creating an environment where the operator can be at their best, shift after shift.

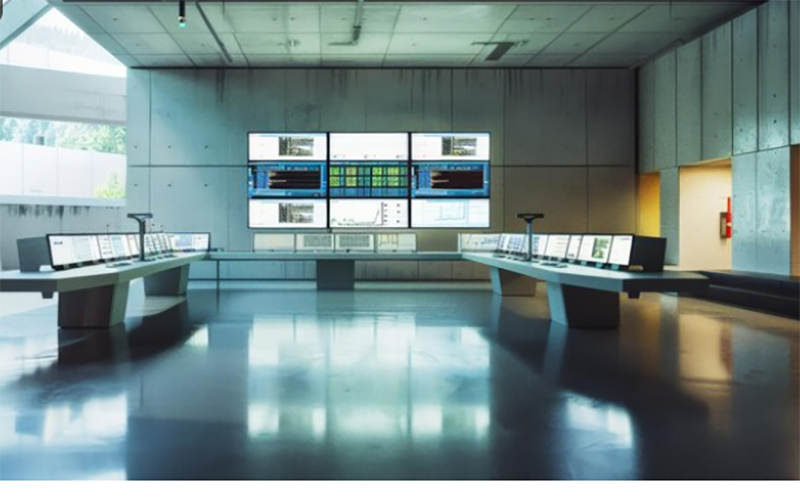

The result is a space that feels intuitive, not imposed. Operators don’t fight the room. They flow through it. Controls are where they expect them. Data appears in context, not chaos. The physical setting recedes into the background, not because it is unimportant, but because it is so well attuned to need that it requires no conscious adjustment.

And in high-stakes environments—where seconds count and errors carry weight—that seamless alignment becomes a silent advantage. It doesn’t announce itself with fanfare. It reveals itself in consistency: in steady performance during night shifts, in accurate responses during surges, in the quiet confidence of a team that trusts not just their tools, but their surroundings.

Of course, this excellence is rarely visible to outsiders. When a city’s infrastructure runs smoothly, credit goes to technology or policy. Few consider the room where humans interpreted data with precision because their environment allowed them to. But those inside know: the space between data and decision was not left to chance. It was designed with care, built with integrity, and refined with respect for the people who occupy it.

In the end, a control room is not a command center. It is a cognitive sanctuary—where data is not just displayed, but understood; where decisions are not just made, but made well. And that understanding begins not with the screen, but with the space around it.